Author

Reviewer

Share Article

PCSK9 inhibitors: For Which Patient and When?

| Author | Reviewer |

|

Shaun Goodman, MD, MSc Co-Director, Canadian VIGOUR Centre, University of Alberta Associate Head, Division of Cardiology, St. Michael's Hospital Toronto, ON |

Milan Gupta, MD, FRCPC, FCCS, CPC(HC) Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto |

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of morbidity and mortality globally, accounting for approximately 1 in 3 deaths. This is largely due to atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), including myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke. Despite the apparent inevitability of ASCVD (if we live long enough!) and the enormous clinical burden, many ASCVD-related events are preventable. Indeed, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is the most common modifiable CV risk factor with robust evidence from trials of lipid-lowering therapies demonstrating a clear, causal relationship between LDL-C lowering and ASCVD event reduction.

LDL-C Lowering: How are we doing in Canada?

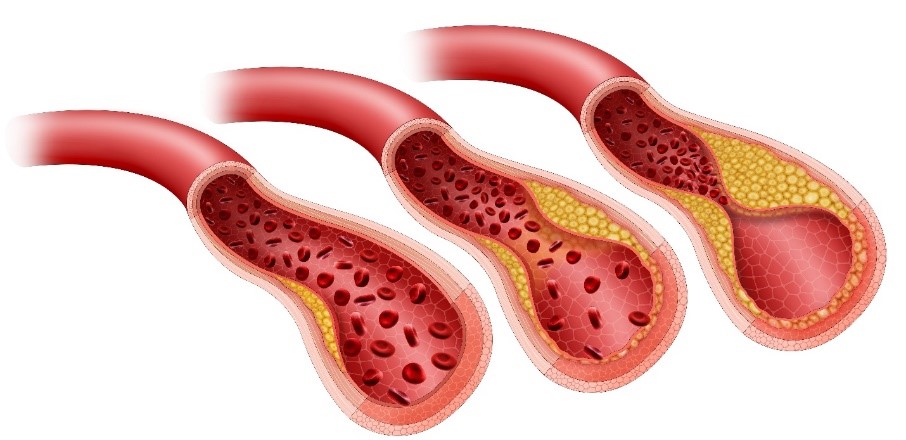

Based on randomized clinical trials demonstrating CV  event reduction, Canadian guidelines recommend a statin as first-line lipid-lowering therapy for LDL-C. However, observational findings have identified large gaps in the clinical care of ASCVD patients: Canadian real-world data (RWD) consistently shows that these patients do not achieve sufficient LDL-C reductions despite statin treatment. For example, only 1 in 2 ASCVD patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for coronary artery disease in Ontario had their LDL-C level measured within 6 months, despite the fact that more than 4 in 10 did not achieve LDL-C goals. Unsurprisingly, over the course of the next 3 years, those with LDL-C levels above the 2021 Canadian guideline-recommended threshold of 1.8 mmol/L had an increased risk for CV events. Thus, I have all of my ASCVD patients undergo lipid profile testing ~4 weeks after any change in LDL-C-lowering therapy, and as a minimum on an annual basis. Further, I attempt to intensify LDL-lowering therapy in those not getting to threshold.

event reduction, Canadian guidelines recommend a statin as first-line lipid-lowering therapy for LDL-C. However, observational findings have identified large gaps in the clinical care of ASCVD patients: Canadian real-world data (RWD) consistently shows that these patients do not achieve sufficient LDL-C reductions despite statin treatment. For example, only 1 in 2 ASCVD patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for coronary artery disease in Ontario had their LDL-C level measured within 6 months, despite the fact that more than 4 in 10 did not achieve LDL-C goals. Unsurprisingly, over the course of the next 3 years, those with LDL-C levels above the 2021 Canadian guideline-recommended threshold of 1.8 mmol/L had an increased risk for CV events. Thus, I have all of my ASCVD patients undergo lipid profile testing ~4 weeks after any change in LDL-C-lowering therapy, and as a minimum on an annual basis. Further, I attempt to intensify LDL-lowering therapy in those not getting to threshold.

![]() What are the updates to the clinical approach to dyslipidemia?

What are the updates to the clinical approach to dyslipidemia?

Beyond Statins: The Efficacy and Safety of Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin–Kexin type 9 (PCSK9) Inhibition

Beyond Statins: The Efficacy and Safety of Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin–Kexin type 9 (PCSK9) Inhibition

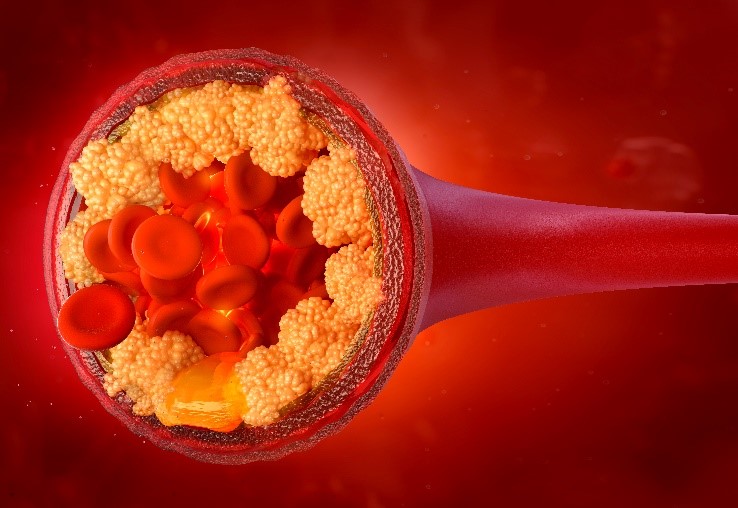

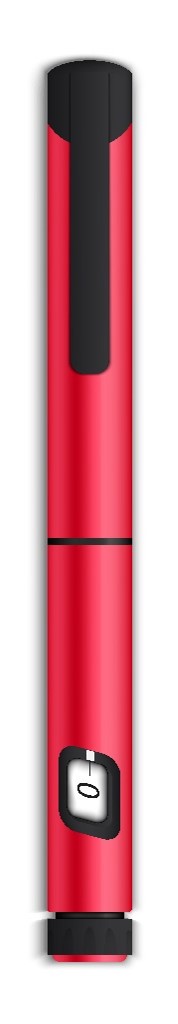

The role for non-statin LDL-C-lowering therapy, particularly among those patients unable to achieve guideline-recommended threshold despite statin, is now well established. For example, evolocumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 (PCSK9), usually administered with a simple auto-injector subcutaneously twice a month. Evolocumab lowers LDL-C levels by approximately 60% and confers important reductions in CV events. Remarkably, apart from 1 in 200 patients noting nuisance local injection site reactions (e.g., redness, itchiness, mild swelling), the tolerability and safety of evolocumab was indistinguishable from that of the placebo group over a 2-year follow-up period in a 27,500-patient trial. Further, there was a direct relationship between the lowest levels of achieved LDL-C and major CV outcomes. Conversely, there were no safety concerns with very low LDL-C levels reached with evolocumab. In conclusion, beyond the previous observations with high intensity statins that “lower is better”, the evolocumab outcome trial clearly demonstrated that “lowest is best”.

In an open-label extension study following the large evolocumab versus placebo outcome trial, extended treatment with evolocumab (in the group initially randomized to evolocumab) was safe, well-tolerated, and associated with fewer CV events and deaths when compared with delayed treatment with evolocumab (in the group initially randomized to placebo). Further, long-term achievement of lower LDL-C levels (down to <0.5 mmol/L) was associated with the lowest risk of CV events, with no safety concerns up to ~9 years.

How effective are PCSK9i at LDL-lowering in real world Canadian practice?

There has been relatively limited RWD  describing the clinical characteristics of Canadian patients prescribed evolocumab. Thus, an observational study was conducted by Canadian clinical practitioners in their patients being initiated on evolocumab and followed-up as part of routine clinical care. Among patients with ASCVD and/or Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH)--more than half of whom were already taking a statin and/or ezetimibe--the addition of evolocumab led to an impressive 60% relative lowering of LDL-C. Almost 8 in 10 patients achieved an LDL-C below the Canadian guideline-recommended threshold of 1.8 mmol/L. Thus, these RWD give us further confidence in the effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibition in real world Canadian practice.

describing the clinical characteristics of Canadian patients prescribed evolocumab. Thus, an observational study was conducted by Canadian clinical practitioners in their patients being initiated on evolocumab and followed-up as part of routine clinical care. Among patients with ASCVD and/or Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH)--more than half of whom were already taking a statin and/or ezetimibe--the addition of evolocumab led to an impressive 60% relative lowering of LDL-C. Almost 8 in 10 patients achieved an LDL-C below the Canadian guideline-recommended threshold of 1.8 mmol/L. Thus, these RWD give us further confidence in the effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibition in real world Canadian practice.

Are PCSK9i as safe and well-tolerated as demonstrated in clinical trials?

Are PCSK9i as safe and well-tolerated as demonstrated in clinical trials?

The vast majority of Canadian patients in the real-world study did not experience an adverse event, and no injection-site reactions were reported. Approximately 1 in 6 patients discontinued evolocumab therapy over a 12-month period, with the most common reason being lack of reimbursement; thus evolocumab therapy persistence was greater than 90%. Thus, you can expect robust LDL-C reductions in patients receiving evolocumab, together with excellent tolerability and a favourable safety profile, similar to that demonstrated in clinical trials.

![]() How has COVID-19 impacted Canadians with cardiovascular disease?

How has COVID-19 impacted Canadians with cardiovascular disease?

Which patients should receive PCSK9 inhibitors in real world practice?

The 2021 Canadian Dyslipidemia Guidelines have now made it clear that ASCVD patients already receiving a maximally tolerated statin dose but whose LDL-C is greater than 2.2 mmol/L (or apolipoprotein B [ApoB] is greater than 0.8 g/L or non-high density lipoprotein-cholesterol [non-HDL-C] is greater than 2.9 mmol/L), require a PCSK9 inhibitor. If the LDL-C is in the 1.8-2.2 mmol/L range (or ApoB 0.70-0.80 g/L or non-HDL-C 2.4-2.9 mmol/L), the patient could be first considered for ezetimibe, since the anticipated 15%-20% relative lowering with this therapy would potentially lower the atherogenic lipoproteins below the guideline-recommended thresholds (i.e., LDL-C <1.8 mmol/L, ApoB<0.70 g/L, non-HDL-C <2.4 mmol/L). However, if the addition of ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin doesn’t achieve these thresholds, we should recommend adding a PCSK9 inhibitor. Finally, the guidelines have identified ASCVD patients who derive the largest absolute benefit from intensification of statin therapy with the additional use of a PCSK9 inhibitor, including those with: a recent (within the previous 1-2 years) acute coronary syndrome (ACS), recurrent MI, diabetes mellitus (or metabolic syndrome), polyvascular disease (i.e., vascular disease in 2 or more arterial beds; e.g., cerebrovascular or peripheral artery disease [PAD]), symptomatic PAD, previous coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), an LDL-C ≥2.6 mmol/L or heterozygous FH, a lipoprotein(a) ≥60 mg/dL (120 nmol/L). Indeed, these types of patients at particularly high residual risk for CV events get the “biggest bang for the buck”—from both clinical and cost-effective perspectives--from PCSK9 inhibitor therapy.

The development of this blog was overseen by the Canadian Collaborative Research Network and was supported through an educational grant from AMGEN.

copyright © 2025 CCRN

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of CCRN.