Author

Share Article

Osteoporosis Management in Primary Care – Anabolic Therapies

| Co-author | Co-author |

|

Jonathan D. Adachi, MD, FRCPC Professor Emeritus, St. Joseph’s Healthcare – McMaster University Hamilton, ON |

Vivien Brown, MDCM, CCFP, FCFP, NCMP

Assistant Professor, University of Toronto, Peer Voice, MDBriefcase, STA Communications; Board Member of Immunize Canada, Women’s Brain Health Toronto, ON |

What are the implications of osteoporosis and fractures?

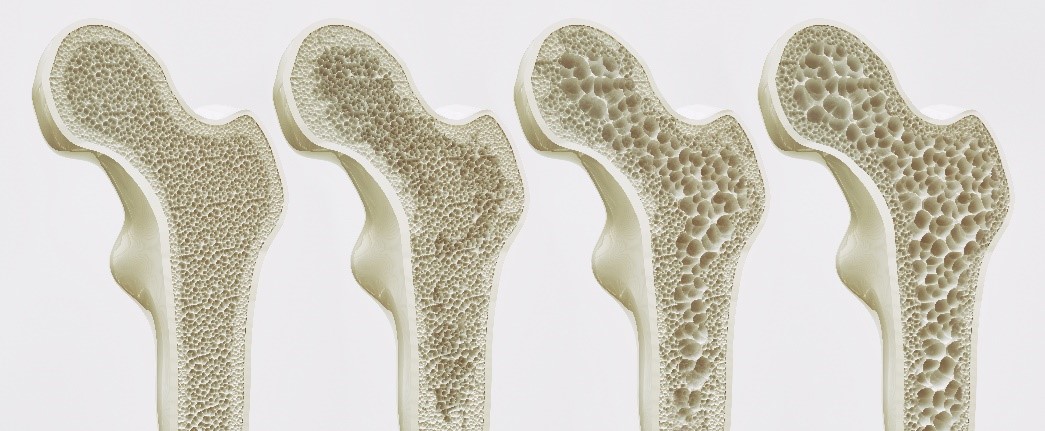

Osteoporosis is characterized as a decrease in bone mass leading to an increased susceptibility to fracture. This has pragmatically been defined as a T-score of less than -2.5 on bone density measurement of the spine or hip. This identifies a set of individuals who are at increased risk for fracture. Fractures are very different in adults than they are in children. In children, fractures are associated with pain and discomfort, inconvenience for a short period of time, and complete recovery. In adults, however, fractures have very different consequences. For those who sustain a hip or vertebral fracture, in addition to the associated pain, there is a 3 to 4-fold increase in the risk of dying. In addition, fractures in adults may lead to chronic pain, further risk for fracturing, institutionalization, and frailty leading to the deteriorating health that we often see in older people.

The implication of a fracture in a mature adult, is the risk of losing independence. Whether we look at data for admission to a long-term care facility, difficulty walking or even mortality increase, an osteoporotic fracture reflects frailty and further risk.

For the osteoporotic patient, a fracture is a bone attack, and has the same implications as a heart attack has to the patient with cardiovascular disease.

Watch this video summary with blog author Dr. Rick Adachi

What do we mean by imminent fracture risk? Why is this important?

Currently we assess fracture risk by looking at a 10-year timeline using tools like FRAX and CAROC. This is most useful in the younger individual in whom we do not anticipate fractures occurring over the next 5 years. Indeed, these are often people around 55 who are otherwise healthy and whose Bone Mineral Density (BMD), even if it were in the osteoporotic range, would place them within the moderate risk range for fracture.

In the older individual, a 10-year fracture risk timeline loses meaning. Many cannot see this timeline occurring in their lifetime. As a result, it is much more meaningful to use a 1-2 year timeline or imminent risk for fracturing. It reflects the urgency to get on therapy to prevent fractures. Not only does this apply to patients, but it reflects the importance of treatment to family members as well as healthcare providers.

![]() What about atypical fractures?

What about atypical fractures?

![]() Which patients should I use PCSK9 inhibitors for and when?

Which patients should I use PCSK9 inhibitors for and when?

How do we identify those at very high or imminent fracture risk?

We can use traditional fracture risk assessment tools like CAROC and FRAX to identify those at increased risk for fracturing over 10 years. Those at very high risk would be those with a FRAX score of 30% or more for major osteoporotic fracture. Unfortunately, despite educational efforts, identification of those who would benefit from treatment remains problematic. Indeed, even in those physicians who have an interest in osteoporosis, these tools are not used. One of the major reasons is that they are not yet incorporated into EMRs and completing the calculations, while relatively easy, means leaving their EMR downloading the FRAX calculator and carrying out the calculation.

As a result, in addition to these tools, I would ask clinicians to remember 3 things that are intuitive in determining fracture risk: age greater than 65 as it reflects those who we consider seniors, BMD less than -2.5 as it is the definition of osteoporosis, and prior fracture as this is the outcome that we are trying to prevent. Of these, fracture is the most important. I consider people at very high risk or imminent risk of fracturing as those who have had a fracture and are either 65 years of age or have a BMD less than -2.5. These are individuals who require urgent treatment. Those who have not had a fracture, but who have a BMD less than -2.5 and who are greater then 65 years of age, should be considered at high risk for treatment. Those who are older than 65 or who have even lower BMDs should be considered at greater risk for fracture.

![]() How do we identify patients at high and very high risk of fracture?

How do we identify patients at high and very high risk of fracture?

Unfortunately, HCPs do not necessarily appreciate the urgency of osteoporosis. The result is osteoporosis prevention drops down the priority list for HCPs as they tackle other urgent chronic disease issues, such as diabetes and heart disease, much more readily. We lose sight of the important fact that the most likely event for a post menopausal woman is a fracture, more likely that CVS, MI or a diagnosis of breast cancer all combined.

Does a change in BMD reflect fracture risk reduction?

In the past, it was felt that a stable BMD or an increase in BMD represented treatment success. While this still holds true we now know that the greater the increase in BMD the greater the fracture risk reduction. As a result, the speed with which we increase BMD may be an important consideration in choosing the appropriate treatment. For example, anabolic treatment with romosozumab will increase BMD in 1 year what it would take denosumab 3-4 years to achieve. This is particularly important for the person who is at very high risk or imminent risk for fracture. Fractures in this population are associated with increased mortality, decreases in quality of life, and increases in frailty.  While hip and spine fractures have the greatest impact, all fractures are associated with increased mortality and decreased quality of life and frailty.

While hip and spine fractures have the greatest impact, all fractures are associated with increased mortality and decreased quality of life and frailty.

![]() How common is ONJ in Osteoporosis patients and how do I manage the risk?

How common is ONJ in Osteoporosis patients and how do I manage the risk?

When would you consider anabolic treatment?

I would consider treatment with romosozumab or teriparatide in those who are at very high risk or imminent risk for fracture. Most recommendations for anabolic treatment are for those who have had a hip or spine fracture, however recent work that we have published suggests that all fractures are associated with an increase in future fractures. Recency of vertebral fracture (within 2 years) is important  and increases the risk of fracture 2-fold, particularly in patients in their 50’s and 60’s. Most experts in the field look at anabolic therapy as building the foundation for further increases in bone mass, after which anti-resorptive therapy with either denosumab or a bisphosphonate will consolidate bone that has been laid down. Indeed, with denosumab further increases in BMD may be seen. Head-to-head studies of anabolic therapy with either romosozumab or teriparatide, compared to anti-resorptive therapy with a bisphosphonate, demonstrate greater fracture risk reduction of up to 40% for hip fracture. Given these results, it is clear that anabolic therapy followed by antiresorptive therapy will be important for those at high or very high risk for fracture.

and increases the risk of fracture 2-fold, particularly in patients in their 50’s and 60’s. Most experts in the field look at anabolic therapy as building the foundation for further increases in bone mass, after which anti-resorptive therapy with either denosumab or a bisphosphonate will consolidate bone that has been laid down. Indeed, with denosumab further increases in BMD may be seen. Head-to-head studies of anabolic therapy with either romosozumab or teriparatide, compared to anti-resorptive therapy with a bisphosphonate, demonstrate greater fracture risk reduction of up to 40% for hip fracture. Given these results, it is clear that anabolic therapy followed by antiresorptive therapy will be important for those at high or very high risk for fracture.

Ultimately, it is important to know that we have a number of excellent tools to identify those that are at high or very high risk for fracture. We have very effective therapies that will quickly reverse bone loss and reduce the risk for fractures. The idea that we should commence anabolic therapy followed by antiresorptive treatment will be important in optimizing care and reducing the risk of fractures.

As physicians we must practice aggressive osteoporosis prevention and aim to keep our patients mobile, independent, and living in the community. To be successful, we need to treat the patient, not merely the fracture, and assess ongoing risk.

Continuing learning with CCRN webcasts and podcasts:

The development of this blog was overseen by the Canadian Collaborative Research Network and was supported through an educational grant from AMGEN.

copyright © 2025 CCRN

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of CCRN.